Lessons from America: Labo(u)r markets & industry

Why two ‘backward’ American states produce more cars each year than the whole UK

Throughout the American Rust Belt – in the Midwest and Northeastern states – factories have closed, and jobs have vanished as industries have declined. But where did those jobs go? Not to China or Vietnam, but to the South.

From 2019 to 2023, the Rust Belt lost roughly 60,000 manufacturing jobs, while Texas alone gained almost 50,000. Jobs that disappeared from Pennsylvania, Indiana, and Ohio didn’t necessarily cross oceans – many of them relocated to states like Texas, Georgia, Tennessee, and South Carolina.

The real story of the American Rust Belt is not about cheap foreign competition taking American jobs. It is a story of states with increasingly rigid labour laws losing out to states – often in the South – that have made their labour markets more flexible.

Take Michigan. It has been the leading car manufacturing state since Henry Ford pioneered mass production. But production there has stalled.

It’s not really China that is to blame but Michigan’s ever more prescriptive labour laws, among other domestic factors. Over the past couple of decades, Michigan has adopted a raft of laws governing health and safety, wage payment schedules, and an array of entitlements. A couple of years ago, Michigan repealed so-called right-to-work laws, restoring mandatory union membership in some workplaces.

In contrast, states like Alabama, Texas, Tennessee and my own Mississippi have far more flexible labour markets. Employers can terminate the contracts of employees for almost any reason (or no reason) without notice, and employees can resign at any time. They obviously have to comply with minimum standards set by the federal government, but they don’t, for the most part, embellish upon them.

The result? Auto manufacturing in such states is booming. Michigan might still be number one, but since 2000 the number of auto manufacturing jobs in the state is down by around 40 per cent. In Alabama alone, the number of auto jobs has now surpassed 50,000, up from just a few thousand in 1997.

Despite all the talk of deindustrialisation in America, the US economy overall produces more manufactured goods today than ever before. Industrial output in the US today is approximately twice what it was when Ronald Reagan was in the White House, and three times greater than when Lyndon Johnson was president.

In Britain, however, labour laws over the past two decades have become increasingly restrictive. Instead of freeing employers to make the decisions for their businesses, the onus is on employers to justify letting staff go. Workers have enhanced protections. EU-era working time regulations remain in place and anti-discrimination laws are stringent. Employment tribunals often seem to side with employees. Resolving employment disputes costs employers billions each year.

This is surely one of the reasons industrial output has grown sclerotically over the past two decades. In 2023, UK manufacturing output was $279bn (8 per cent of GDP) compared to $237bn (12 per cent of GDP) in 2003.

Of course, labour markets are important not only for industrial jobs, but for every sort of employment.

Flexible employment laws generally mean more employment – which is partly why America has been so good at creating jobs in the first place. And those jobs seem to have been disproportionately created in states with more flexible labour laws.

Industrial jobs might have moved South in America, but so have many other types of employment. Since 2020, more than 150 financial firms, managing trillions of dollars, have relocated operations from the likes of New York and moved South, notably to Florida and North Carolina. JP Morgan Chase, one of America’s largest banks, now has a larger work force in Texas than in New York state.

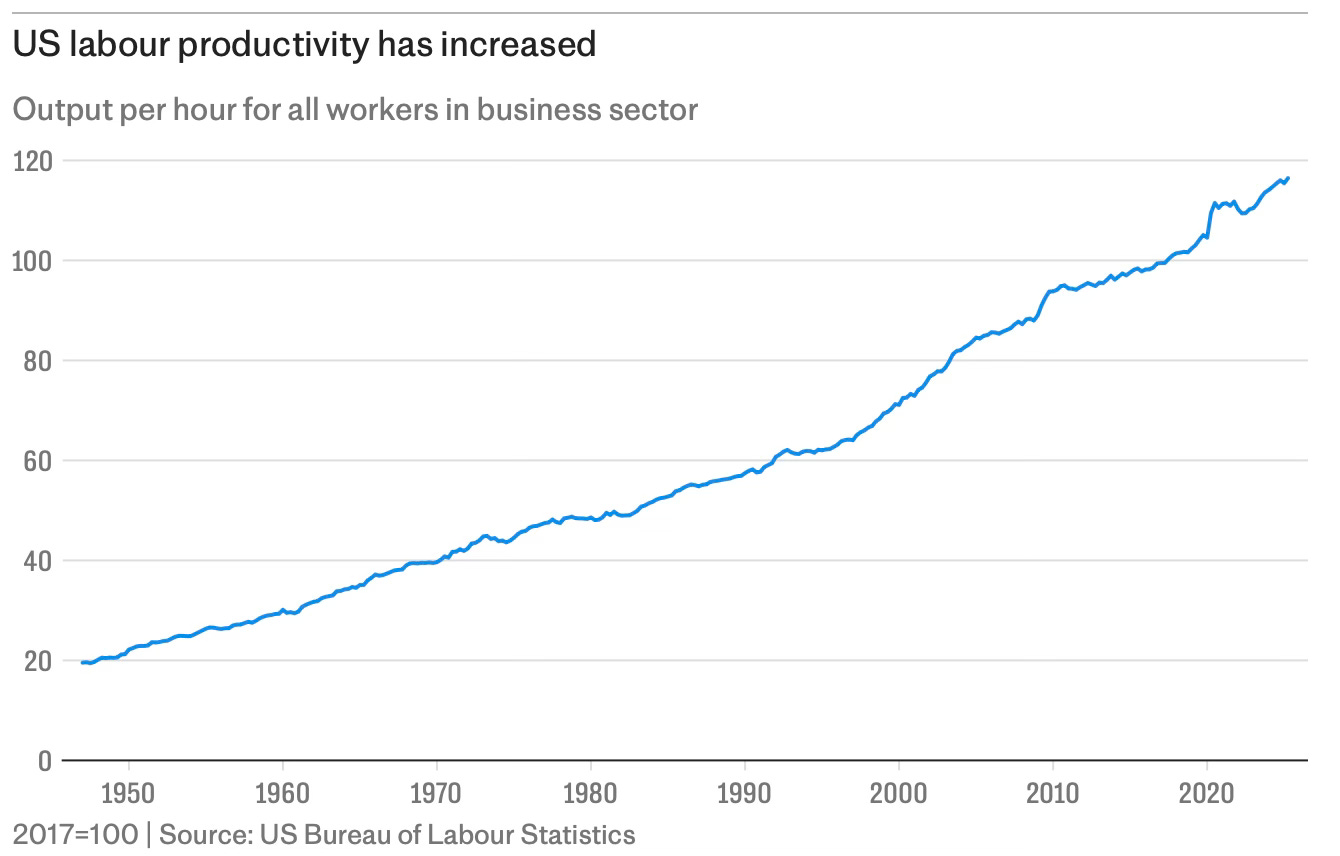

Light touch labour laws also mean more jobs that can sustain a higher living standard. American workers are so much more productive that they are able to earn significantly more. By 2021, a British study estimated that a UK worker produced on average £46.92 per hour worked. Their American equivalent generated £58.88, approximately 20 per cent more value.

Since 2010, the productivity of American workers has improved by about 23 per cent. That essentially means for each hour worked, they are generating almost a quarter more. In the UK, by contrast, productivity has risen by less than 10 per cent. In large public sector organisations like the NHS, productivity has actually fallen in recent years.

Britain’s productivity performance over the past two decades has been dire, and all sorts of efforts have been made to address this, from Boris Johnson’s Levelling Up initiative to building high speed rail networks.

If Britain really wanted to boost productivity, a good place to start would be labour market reform. Having a flexible workforce allows firms to quickly adjust staffing to match demand, reducing idle labour and boosting output per worker.

When productivity increases, this also tends to push up wages. British wages were roughly on a par with those in the US 20 years ago. Factoring in lower US taxes, net wages in America may now be 40-50 per cent higher than in Britain.

And while the Left might expect workers to be fleeing states it considers to engage in exploitative labour practices, better living standards are a key reason why the opposite is occurring. States with more flexible markets have been among those enjoying the strongest population growth in recent years, as families leave tightly-regulated areas in the Northeast and Midwest for better opportunities in the South.

Britain desperately needs to learn the lessons of what works in America, and introduce, among other changes, a 90-day “at-will” dismissal period for new hires, allowing termination without cause, modelled on US employment law. Like Mississippi, and other southern states, it needs to make a concerted effort to remove many of the occupational licencing rules that, according to the Social Mobility Commission in 2024, mean some sort of licencing is required for 29 per cent of occupations, impacting almost a quarter of the workforce.

Post-Brexit Britain should stop comparing itself to the European Union, whose labour markets are even more inflexible, and deindustrialisation even more pronounced. Instead, British policy-makers should look to Texas, Tennessee and Mississippi labour reforms if it wants to have an industrial future.

Mississippi and her neighbour Alabama, two states with a combined population of about nine million that have regularly been dismissed as economically “backward”, are now estimated to produce more cars each year than the whole of the UK, with a population of 69 million. Perhaps instead of ignoring their lessons, British politicians should accept the evidence staring them in the face.